Monday, January 25, 2010

We Dat

Sure, it's just a football team, just a game. But there is nothing in life quite like the feeling a loser has when he wins. It's the sort of thing that can change a life, by going all the way down to where identity is formed. Right now, it feels like the sort of thing that can change the course of history for a whole people. Failure as an identity is the severest handicap of all. To get a glimpse of what life is like as a winner after a lifetime of failure (real or, sometimes even more difficult, imagined) can be transformative. Not as inspiration, but as identity. That what the Saints win means for all of us Who Dats - the intoxicating feeling of success is a good in itself but it also brings a sense of hope that we can change for the better. As a community act, the city's celebration of itself last night and now has maybe already changed us by giving us a sense that in our individual and collective identity we're not failures after all, we're just us, and that's feels pretty good just now.

Friday, January 22, 2010

a big week for "I"

A Supreme Court decision eviscerating Congress's now-failed attempt to limit the effect of corporate money on elections; an electoral rejection of a Massachusetts Democrat on grounds that health care for all will cause an incremental increase in taxes : it's been a tough week for those of us who persist in the belief that our society moves over time towards an ever more rational, ever more ethically-minded sensibility about how best to configure ourselves relative to each other as a society. Maybe the U.S. is too far down the path of the glory of self-interest to realize that there is no virtue in equating the interests of corporations - groups of people organized for the sole purpose of earning profit - with our society's best interests. True, the creation of wealth is a 'good' and necessary aspect of life. But accepting that wealth creation is the solution to all societal problems is just wish fulfillment, and an easy convenient answer for us, a way to avoid facing real problems. Allowing an insurance industry whose sole purpose is to extract profits from health care transactions between providers and consumers to regulate and increasingly define those transactions in ways best configured to produce profit is to do one thing only - produce insurance industry profits. Providing health care for poor people is simply not profitable, so it is not provided. We are now coming to see that providing health care to really sick people is not profitable, either, so slowly the industry is finding ways to avoid providing it (preexisting conditions, etc.). But under the mantra of freedom (the freedom to produce wealth), we seem to be reluctant to do anything to redirect the system to more efficiently define the provider-consumer transaction. And the same political system which is in the process of refusing reform is also telling us that we cannot do anything about it : we cannot even, thorough Congress, regulate the control corporations have over the political process. So, it appears that we are headed irreturnably down the rabbit hole of self-interest with nothing more than the unfounded belief that producing wealth is more than enough of a societal benefit to offset the consequences of ignoring the inefficiencies of a profit-driven system rather than a needs-driven system. And nobody, it seems, cares. Everybody is too busy either making money or spending it. Everybody, that is, except the people who have needs left unaddressed by profit-makers. Is this really what we want for ourselves, as a society ? Do we really want, "Every man for themselves" ? I don't think we do. I still trust that people in this country are going to wake up one day and realize how far removed we've allowed ourselves to get from the notion that we are our best when we see life as "we", not as "I".

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

we want the good times, not the money

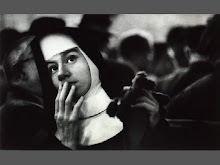

There is a distinctly Catholic aspect which contributes to the character of the New Orleans citizenry. A judgmentalism founded in the ethos of a uniquely personal responsibility to God and self prevails in most of the U.S., the result of a Protestantism in which each individual's relationship to God is self-determined. Inevitably this has produced a society of individuals who each consider themselves exalted to one degree or another, informed only by their own notions of themselves and encouraged by the world's reward system to think that advancement of their own material interests is not only their loftiest goal but also their ethical responsibility. New Orleans, however, is different, in that (among many other things) its people seem not to care so much for personal advancement as they do for enriching experiences. Experiences, though, by definition, are contingent, and this to me may be key to understanding what makes us different. There is a strong component of contingency in the Catholic faith : salvation is temporary and redeemable in that we acknowledge our failings through confession, so the "what's here today may be gone tomorrow so why bother" ethic seems to me to be ingrained in how we think about ourselves. A result of understanding and accepting our failings (instead of denying them or correcting them) is that we as a community are more indulgent of others' failings, and indeed more accepting of material circumstances which would be deemed unacceptable anywhere else in the U.S. So maybe almost 300 years of the principles of sacramental confession have helped shape our community personality to produce the laissez-faire ethos which still defines us.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)